Because Islam developed in wildly disparate areas, each with its own cultural traditions, Islamic art encompasses a tremendous variety of motifs, materials, and styles. One element common to all Islamic art is the absence of human form, as any attempt to imitate God’s divine creation is considered idolatrous and blasphemous. As a result, Islamic artists developed a non-representational artistic language, Calligraphy, floral arabesques, and geometric motifs cover everything from mosques and pottery to metalwork and wood carvings.

THE MOSQUE

The cami (Turkish for “mosque”) represents the most significant architectural manifestation of Islamic art. As the religious, political, and social center of the Islamic world, mosques often housed schools and libraries in addition to religious facilities. The earliest mosques, based on the layout, of the Prophet Muhammed’s house in Medina, were simple and functional: large, square prayer halls with open central courtyards. The expansion of the Islamic empire saw the assimilation of Persian, Roman, and Byzantine motifs, which transformed the simple Arabian mosque into a complex affair of tiled domes, vaults, and arches.

The minaret is attached to the outside of the mosque. Originally a small elevated platform, but now a conical tower, it is used by the muezzin (crier) to belt out the adhan (call to prayer) five times daily. The minarets of most mosques are nowadays equipped with speakers for extra amplification. The mosque courtyard often features a şadirvan (fountain) for ritual washings (ablutions) performed before prayer. Inside, the congregation faces the mihrab, a niche in the qibla, or wall that the congregation faces when praying. To the right of the mihrab is the minber, a wooden staircase from which the Imam (spiritual guide) gives the sermon.

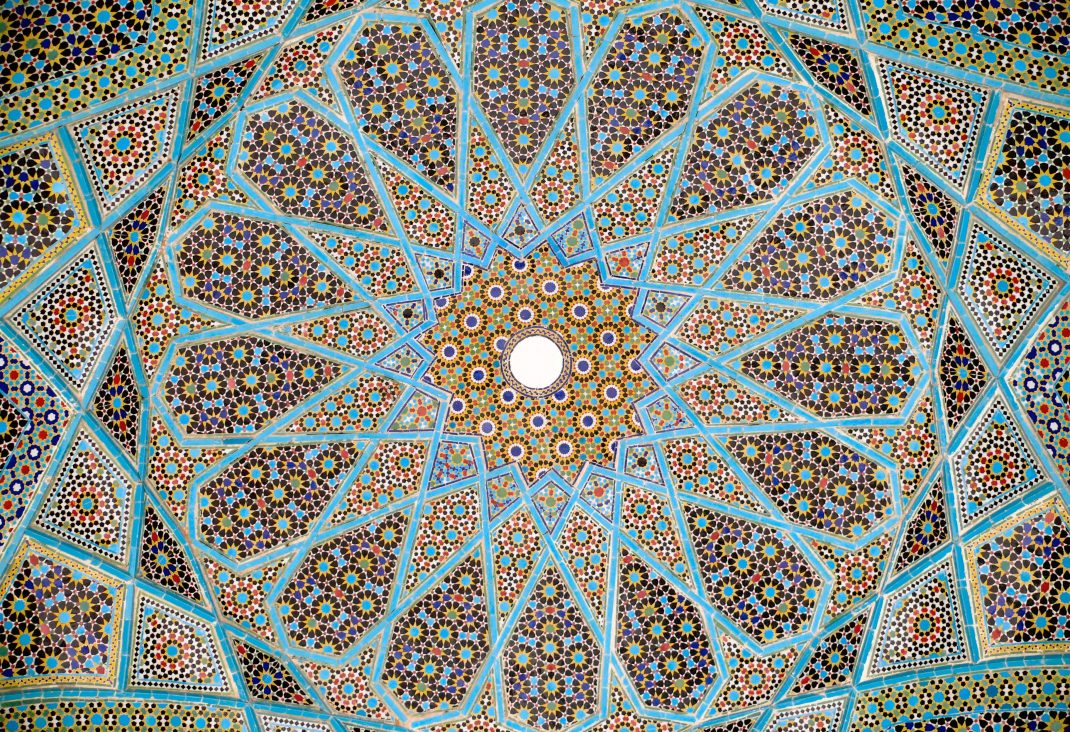

All mosques feature spacious, oasis-like interiors either an airy domed space or an open-air courtyard flanked by cool porticoes. With their roots in Persian and Byzantine models, domes are a common feature of mosques. They use a dazzling variety of structural supports to transform the corners of the square base into an octagonal opening for the dome.

Mosques often formed the centerpiece of a larger complex of buildings, and were often flanked by a medrese (theological seminary) and türbe (tomb). Under the Ottomans, the complex surrounding the mosque developed into a vital social center that served all of a community’s needs.

SELÇUK ARCHITECTURE AND DECORATIVE ARTS. During the heyday of the Sultanate of Rum, Selçuk architects undertook extensive public works projects. Using the abundant Anatolian stone and clay, they built mosques, medrese, and türbe. Rum Selçuk architects modified the designs they inherited from their Iranian counterparts with elements of Syrian and Byzantine architecture, keeping the strict Iranian rectilinear mosque and medrese plan and the decorated minarets.

To safeguard their profitable trade in silks, spices, and slaves, and to provide rest for merchants, the Rum Selçuks built over 100 kervansaray, or hans, along Anatolian highways, each spaced a day’s ride away from the next. These rest stops featured mosques, storage rooms, stables, coffeehouses, hamams, private rooms, and dormitories. The most impressive example of Selçuk Hans is the Sultan Han outside Kayseri.

Rum Selçuk buildings were characterized by their elaborate stone carvings. Earlier carvings reflect the geometrical asceticism of Syrian and Persian designs, while later carvings, such as those on the facades of Sivas buildings and on Konya’s İnce Minareli, burst into exuberant arabesques and Baroque flourishes. In addition to carvings, the Selçuks enhanced their mosques and medreses with glimmering/crience (glazed earthenware). The fruit of Iranian craftsmen, Selçuk faience was used to cover walls or minarets, with the best examples at Konya in the Karatay Medrese.

Under Selçuk patronage, decorative arts enjoyed a boom, which was later halted by the 13th-century Mongol invasion. Glassware and textiles were regular staples of commerce, while new techniques in ceramics and lustre painting created more opportunity for the use of faïence. The school of metalworking was particularly important, churning out engraved, silver inlaid candlesticks and bowls.

OTTOMAN ARCHITECTURE

The first Ottoman capital, Bursa, is a museum of 14th- and 15th-century Ottoman architecture, combining elements borrowed from Selçuk and European architecture. With the capture of İstanbul in 1453, Ottoman architects were challenged to outdo the vaults and pendentives of the Aya Sofia’s spectacular dome. Ottoman architecture reached its pinnacle under the unprecedented patronage of Sultan Süleyman. During Suleyman’s rule alone (1520-66), over 80 major mosques and hundreds of other buildings were constructed. Divan Yolu, Istanbul’s processional avenue, boasts a spectacular collection of these structural wonders. The master architect Sinan served Süleyman and his sons as Chief Court Architect from 1538 to 1588, during which time he created a unified style for all of Istanbul and for much of the empire. Trained as a military engineer, Sinan forged an architecture influenced by early Islamic and Byzantine styles. His masterpieces, the Süleymaniye Camil in Istanbul and the Selimiye Camii in Edirne, exemplify the harmonious, multi-domed Ottoman trademark style.

Many Ottoman mosques stand at the center of a külliye (complex) designed to serve all of a community’s needs. Külliyes often included a medrese, a market, a soup kitchen, a kervansaray, and a medical center, all integrated architecturally into a single whole. The most impressive külliyes are the Süleymaniye, in Istanbul, and the Beyazıt,, in Edirne. Most külliyes were established as charitable foundations. Although economic instability has jeopardized these institutions financially, many of them are still functioning.

Sixteenth-century Ottoman architects set a powerful precedent for future structures. Buildings like the Blue Mosque were mere imitations of the Sinan blueprint. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Ottoman architecture, inspired by the fashions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, appropriated an ornate, Baroque style, evident in Istanbul’s flashiest eyesore, the Dolmabahçe Palace.

OTTOMAN DECORATIVE ARTS

The height of Ottoman decorative arts was tile work. From the 14th to 17th centuries, the Ottomans imported Persian craftsmen in order to develop their ceramic industry in İznik, but by 1800 manufacture there had virtually stopped. After a 400-year boom, the ceramics industry in Kütahya has experienced a tourist-driven renaissance.

MODERN TURKISH ART

Long before Atatürk’s revolution, Ottoman painting had gradually begun to adopt Western forms, thanks to the influence of European artists working at the Ottoman court. In 1883, the Academy of Fine Arts was founded by Ottoman artist, museum curator, and archaeologist Osman Hamdi Bey, a man thoroughly Westernized in his painting technique as well as in his educational philosophy. Referred to as the Academy, the Academy of Fine Arts has had a huge influence on Turkey’s major artistic movements: the Çallı group of the 20s, the ‘D’ Group of the 30s, and the New Group of the 40s, 50s, and 60s. Many of the artists who created these movements later became professors at the Academy, and their work is on display at the Painting and Sculpture Museum in Ankara (see p. 398).

In 1914, in response to the demands of the elite, the Ottoman government opened an Academy of Fine Arts for Women headed by painter Mihri Müşfil Hamm, whose work blended İstanbul’s conservatism with a Parisian flair for Levantine fashions. In 1926 the Women’s Academy merged with the Academy of Fine Arts, and has since produced four generations of recognized women painters.

CARPET-MANIA

Turkey is world-renowned for its beautiful carpets. The traditional Turkish double-knot first emerged somewhere between the 4th and 1st centuries BC, while hand-woven carpet techniques were brought to Anatolia by the Seljuks in the 12th century. In the past, village women wove carpets for their personal use; today, most work for shops at the whim of the market. Although many traditional Turkish rugs appear to use uniform patterns such as the diamond like “eye” colors and materials can in fact produce subtle but important variations. For the shopper, beautiful carpets and kilims (double-sided flat-woven mats) can be had in Turkey, but don’t expect a great bargain: it may be cheaper to buy your Turkish carpet back home.

Leave a Reply