Travelers lured by Deyrul Zafarin Monastery to this hilltop city of elegant stone houses perched at the edge of the Syrian desert will discover there is much more to Mardin. Though a perennial hotbed of Kurdish separatist activity, this frontier town lies dormant again, allowing tourists a glimpse of one of Turkey’s most intriguing populations. A 10,000 year heritage has woven a patchwork of different cultures together in this upper Mesopotamian city. Even today, Syrian Orthodox goldsmiths and Muslim copper workers beat out their trades side by side.

Diyarbakır is one of the world’s oldest cities, a fact immediately apparent to any traveler who arrives at this ancient maze of cobbled streets, perched on the shores of the Tigris River in the crook of the Fertile Crescent. The black basalt walls which encircle the city 5km long and reportedly visible from space—are of Roman and Byzantine construction, a relatively recent addition in a place whose archaeological record shows evidence of continuous occupation spanning 7,500 years and 26 distinct civilizations.Nowadays the crescent isn’t so fell tile, but the Tigris floodplain still yields bushels of Diyarbakir’s famous 50kg watermelons—a welcome treat in a town whose summer heat is regularly above 43°C. Two million citizens, half refugees, live submerged in a timeless cacophony of commerce, and the echo of car horns, hi recent years, a massive influx of displaced Kurds has created a second Diyarbakır, this one surrounding the old city walls. To Kurds, Diyarbakır is Amed, their proxy capital. For a people without their own state, the walls offer sanctuary within a sea of perceived repression and injustice. On the surface, Kurds and Turks embrace as brothers. Yet while Kurds cannot carve out a land for themselves, their dreams simmer like the horizon.

Artvin is stapled onto a mountainside, overlooking the vast Çoruh River Valley and at the top of a 5km series of switchbacks chiseled into the western slope. The rarefied Artvin air is saturated with smog and waste, sustaining a beleaguered mix of military men, college students, shopkeepers, and prostitutes. For most of the year, Artvin offers little to the visitor except a few tawdry gazinos and a dubious nightlife. For one shining weekend in late June/early July, however, it is home to the monumental Kafkasör Festival, Turkey’s largest and most authentic folk festival. The festival takes place in a grassy yayla above town, and its bloodless bullfights, folk dancing, and general hijinks attract a diverse and joyful crowd. Artvin is also the capital of a province stretching from tire border with Georgia to the highlands of the Çoruh River, making it a useful travel route inland and a base for supplies for exploring Yusufeli end route to the valley beyond.

The lush hills of Rize rise dramatically from its black pebble seacoast. in steaming terraces, carpeted with tea plantations and tropical gardens. In a country where the daily rhythm is measured in the clinking of çay glasses, Rize is the leading city of tea, a role which commands capital, technology, and respect. With a population over 60,000, Rize is the easternmost major business center on the Black Sea Coast; as an international port town, its streets are packed with an eclectic mix of Azerbaijanis, Russians, and Georgians. Rize has had a long history at the hands of the Black Sea Coast’s many rulers; most architectural traces of that history, however, have been lost in the city’s concrete modernization. Still, in Rize’s hills, travelers can find solace in çay gardens perfumed with night blossoms and aromatic tea.

Halfway up the Upper Fırtına Valley from Çamlihemşin, sleepy Şenyuva is all but hidden from the casual visitor. The valley itself is empty, and the town’s houses and storefronts are shaded by the trees of the high valley walls. Elderly men sit drinking tea and dogs sleep undisturbed on the winding gravel roads; the loudest noise is that of the river cascading through the valleys. Şenyuva’s slow, secluded character offers a relaxed and unobtrusive perspective on traditional and contemporary Hemşin life: over a cup of çay or an impromptu performance, locals are all too happy to discourse on what it means, now and forever, to be Hemşin. Şenyuva offers a first-hand lesson in both contemporary and traditional Hemşin life, and makes an excellent base for trekking excursions.

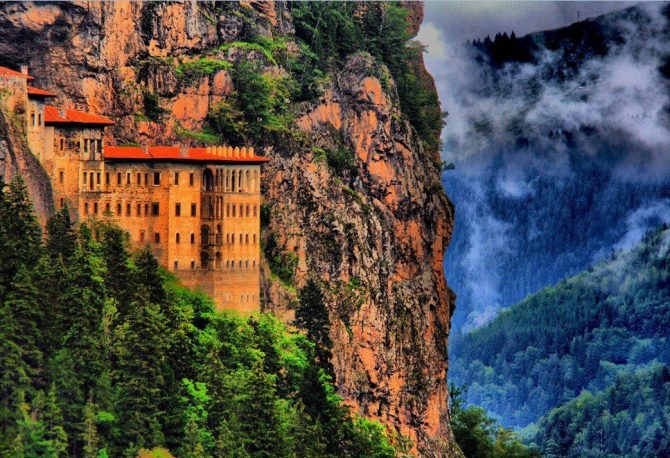

Trapezus, Trebizond, Trabzon: this city has a rich history and the names to prove it. Contemporary Trabzon is one of Turkey’s most cosmopolitan cities. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reopening of Turkey’s northeastern borders, Trabzon has resumed its role as an important trade and transport hub for Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran. Russian influence is inescapable: Cyrillic lettering competes for prominence with Turkish, and Russian restaurants are almost as easy to find as local ones. While thousands of immigrants helped create an economic boom, the entrepreneurs were also joined by a considerable number of prostitutes, most from the former USSR, who form an inescapable part of the mosaic between the city’s Central Square and the Russian bazaar. Trabzon pulses with the dynamic energy of a large border town, and yet is small enough for visitors to appreciate its warmth and explore much of its rich landscape on foot.

Trabzon’s history as a commercial port and hilly refuge dates back to the ancient Greek colonists of Miletus, who dubbed their new community Trapezus. During the Greek and Roman periods, Trapezus grew to a commercial center of international scope. Under Alexius Comneni, who sought refuge here from the Crusaders during the sack of Constantinople, the city reached its heyday as the capital of the Trebizond Empire. His dynasty became the longest-lived, and one of the wealthiest, in Greek history its rulers lived off the profits of trade and local silver mines. The kingdom held out against the Ottomans until 1461 (even longer than Constantinople), when it was seized by Mehmet the Conqueror. Under Ottoman rule, the churches were converted to mosques, and Islam became the dominant religion. Trabzon was invaded by Russian forces in 1916, but was reclaimed by the Turks in February 1918. The city has been growing ever since, and with nearly 1.5 million busy residents, it shows no signs of looking back.

Moving east and inland from Rize, the Kaçkar mountains become steeper and more lush, and their inhabitants become distinctly Hemşinli . The physical characteristics of the valleys as are unique as the cultures they contain: a shocking diversity of flora and fauna in the steaming forests of the lower valleys gives way to the misty moors of the upper grasslands. To move up or down the valley is to follow the seasonality of traditional Hemşin life: from the winter villages at the base to the spring yaylas of the foothills and the summer yaylas in the alpine meadows of the Kaçkars themselves. At every altitude, steeply-pitched stone bridges cross the valleys, and locals and their visiting relatives do then- best to make travelers feel at home, pointing them in the right direction for anything from short walks through the hazelnut trees to longer treks over some of the most striking peaks in the Kaçkar Dağları. Plentiful rainfall characterizes this region, so bring waterproof gear and sturdy footwear. Stinging nettle undergrowth necessitates long trousers and sleeves (see Trekking in the Kaçkars)

A thriving outpost in the dry expanse of Anatolia, Sivas was founded by Hittites in 1500 BC. The city saw the successive rule of Assyrians, Persians, Romans, and Byzantines before flourishing under the control of the Selçuk Sultanate of Rum. Sivas still bears the marked imprint of the Selçuk architectural style. In modem Turkish history, Sivas is renowned as the site of the Sivas Congress of September 1919, during which Atatürk sought to fortify Turkish resistance against Allied attempts to partition Anatolia. The traveler arriving at the outskirts of the city would never guess that hidden among the squat, cement-and-glass cityscape are the intricate geometric patterns of one of the best-preserved collections of Selçuk architecture in Anatolia. In addition to being a center for kilim production, Sivas is also famous for its massive sheepdogs, bred for power and vigilance and exported to shepherds across Turkey.

This beautiful coastal city (pop. 105,000) proudly emphasizes its independence and differences from its grittier neighbor, Trabzon. Giresun is large enough to have a good range of hotels, nearby nightlife, and beaches, but small enough to allow visitors to explore on foot and enjoy a relaxed holiday environment. Giresun can also serve as an excellent, base for exploring many nearby yaylas: mountain communities which offer clean air, a cooler climate, and stunningly lush landscapes.

Giresun has an ancient, history’. Thought to have been founded in the 8th century BC, its original name was Kerasus, meaning “cherry.” It is from here that cherries were introduced to Europe. There is a public circumcision (sunnet) festival here in July, but more interesting (depending on your taste) is the Aksu Festival, held on May 20. This elaborate pagan fertility ritual, said to have originated in Hittite days, heralds spring and the sowing of new’ seeds. Participants pass under several iron rivets and circumnavigate the nearby island, throwing 15 stones overboard to symbolically cast away the sorrows of the past.

Built in the shadow of a huge hill called Boztepe, Ordu is a good base from which to visit the glorious yaylas (highland plateaus) that rise up farther inland. Its selection of budget hotels is limited, however, and apart from a restored Ottoman house cum ethnography museum, there are few’ sights to speak of: a fire destroyed the old town in 1883. A leading world producer of hazelnuts, Ordu hosts the Golden Hazelnut Festival (Fındık Şenliği) in late June and early July, which includes folk music and singing contests.