Now surrounded by arid plains, Miletus once sat upon a thin strip of land surrounded by four separate harbors. Envied for its prosperity and strategic coastal location, the city was destroyed and resettled several times. Eventually, it suffered the same fate as its Ionian neighbors the silting of its harbors. For centuries, Miletus was a hotbed of commercial and cultural development. In the 5th century BC, the Milesian alphabet was adopted as the standard Greek script. Miletus later became the headquarters of the Ionian school of philosophers, including Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes. The city’s leadership, however, faltered in 499 BC, when Miletus organized an unsuccessful Ionian revolt against the Persian army. The Persians retaliated by wiping out the entire population of the city, massacring the men and selling the women and children into slavery.

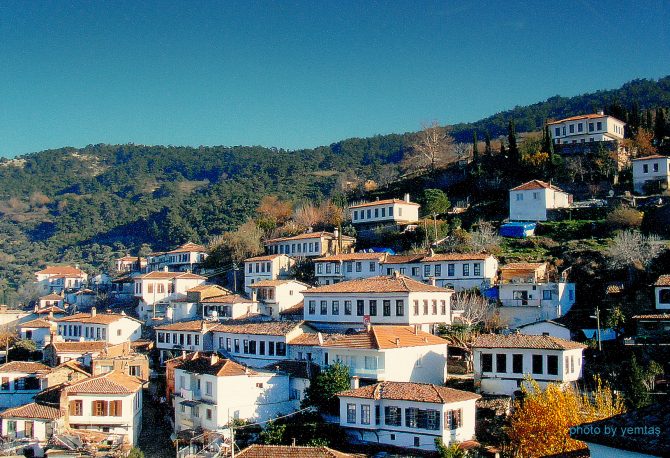

Named for the pigeons that make their home in the town’s 14th-century Genoese castle, Kusadasıi(“Bird Island”) could hardly have escaped the intense tourism it has received. These days, Kusadasi is an unabashed tourist town, catering to foreign travelers of all stripes. Its picturesque setting on sea-sloping hills, excellent, sand beaches, and proximity to the magnincent archeological wonders at Ephesus, Priene, Miletus, and Didyma ensured its transformation a few decades ago from a quiet town to a grand resort. Kusadasi’s broad tourist apparatus accommodates every group. Backpackers arrive by ferry from Samos and by bus from the north, and wealthy American and European tourists flood the carpet shops whenever their luxury cruise liners dock in the small harbor, dwarfing other ships and from a distance the town itself. Excellent budget hotels and towering, four-star luxury palaces are surrounded by myriad high-end jewelry and carpet shops. As many as 100 pubs dot the city.

The dolmuş ride to Söğüt alone is enticing enough to make the journey out to this village just south of Bozburun worthwhile. A well-kept travel agent’s secret, reserved only for the most astute customer, Söğüt has an untouched wealth of beauty to be found in its tiny pebbled beach, surrounding mountains, and breathtaking islands jutting from the miniature bay. The village is spread along the coast and divided by a ridge. Unique in its intimacy, Söğüt also boasts the best fish on the Marmaris coast.

Bozburun lies in a small valley surrounded by the rocky dry hills of the Datça Peninsula. Set against the harbor, Bozburun is a peaceful place for strolling along the waterfront, watching shipwrights assemble the skeletons of embryonic yachts and just enjoying the motion of the ocean. While locals simply jump off tire rocks into the sea, timid tourists may prefer the small beach to the right of the harbor.

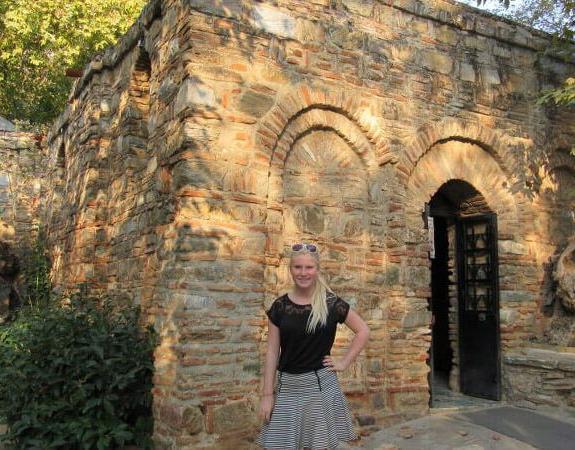

Selcuk is tire most convenient base from which to explore nearby Ephesus, and offers several notable archaeological sites of its own, as well as a glut of carpet shops serving or preying on the large number of tourists who pass through the town every’ year. Selcuk’s Byzantine Castle dominates the skyline, though it is closed indefinitely for restorations. The İsa Bey Camii, the ruins of the Temple of Artemis, and the Basilica of Saint John, where the apostle is buried, lie just below. The House of the Virgin Mary (Meryemana), where Mary supposedly lived out her last years, can also be reached from Selcuk. The town is home to the famous Camel Wrestling Festival, held annually during the third weekend of January near’ Pamucak Beach, a short dolmuş ride away (contact the tourist office for info).

The next cove down the coast from Marmaris, İçmeler is slowly becoming as crowded as its more famous neighbor. The full-blown concrete conglomerate of tall luxury hotels and neon-signed restaurants now runs all the way down to the beach. It’s possible, however, to overlook the package-tour feel of the place and discover İçmeler’s superior beach and watersport options. You’ll also find some quiet, laid-back pensions a pleasant distance from the beach-front, resorts. Frequent dolmuş service to Marmaris, only 10 to 15 minutes away, makes İçmeler an alternative to lodging in Marmaris while staying within reach of its bars and clubs.

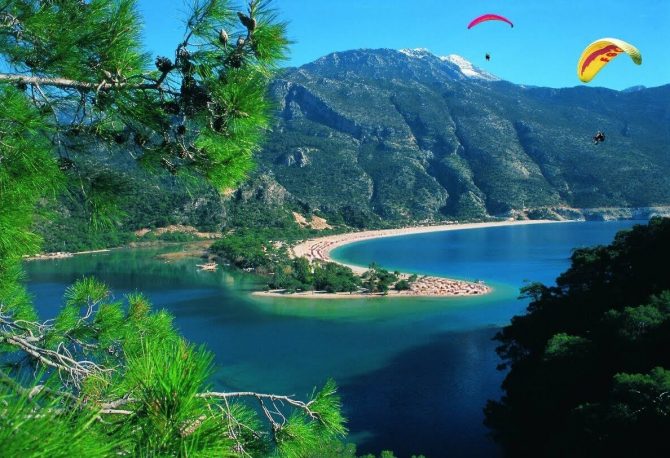

Alternately chic, garish, and remote, Turkey’s Mediterranean coast stretches along lush national parks, sun-soaked beaches, and pine forests. Natural beauty and ancient ruins have made the western Mediterranean one of the most touristed regions in Turkey. While increasingly over-run with pushy touts, Armani sportswear and mega-hotels, the western coast also caters to the backpacker circuit. By day, travelers take tranquil boat trips, hike among waterfalls, and explore submerged ruins; by night, they exchange stories over Efes beer, dance under the stars, and fall asleep in seaside pensions and treehouses.

Stretching from early archaic times to the 6th century AD, Ephesus’s glorious prosperity has not gone the way of other notable ancient cities’. To this day, Ephesus boasts a concentration of Classical art and architecture surpassed only by Rome and Athens. As both the capital of Roman Asia and the site of a large, wealthy port, Ephesus accumulated almost unparalleled wealth and splendor, the marble specter of which still leaves visitors in awe. The ruins rank first among Turkey’s ancient sites in terms of sheer size and state of preservation. No piles of weed-ravaged rubble await imaginative reconstruction work here. Instead, extensive marble roadways and columned avenues create an authentic impression of this ancient, metropolitan gateway to the Eastern world. The best time to visit is right when it opens, before the scorching midday summer sun and throngs of tourists obliterate the last remnants of lingering nighttime cool and silence.

A breezy seaside village, Cesme was built around a 14th-century Genoese fortress that was expanded and beautified by 16th-century Ottomans. A little over an hour from Izmir, the town has deservedly gained popularity for its cool climate, crystal clear waters, and proximity to the Greek island of Chios. Daytrippers from Chios keep the myriad restaurants and leather shops in business, and the affluent Izmir it’s who have weekend houses here ensure an active nightlife in the cafes and bars along the marina. Summer is festival season in Cesme, as the town hosts the Sea Festival/International Pop Song Contest at the end of July and the Cesme Film Festival at the end of August. For the song contest, bars stay packed, and primary sponsors TEKEL (the state alcohol and tobacco monopoly) and Coca-Cola set up tents along the waterfront for giveaways and contests. Information regarding exact dates for these week-long festivals is available in the tourist office.

Izmir (pop. 4 million), formerly ancient Smyrna, has risen from a tumultuous past to become Turkey’s third-largest city and second-largest port. Reputedly the birthplace of Homer, Smyrna gained prominence in the 9th century BC and thrived before Lydians from Sardis destroyed it about 300 years later. In 334 BC, Alexander the Great conquered the city and refounded it atop Mt. Pagus, now called Kadifekale. During the Roman and Byzantine periods, Smyrna reemerged as a prosperous port. The diversion of the River Hermes protected the harbor from silting up, saving Smyrna from the landlocked fate of its stagnating neighbors. In 1535, Süleyman the Magnificent signed a treaty with France, bringing trade to Smyrna. Beginning with the influx of Christian and Jewish merchants, the city had become a haven for migrants from mainland Greece by the 19th century.

After the Ottoman defeat in World War I, the Greek army occupied Izmir in hopes of uniting the area with mainland Greece. Turkish nationalist leader Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) defeated the overextended Greek forces who had exhausted themselves in the Anatolian heartland. Greek troops left Smyrna on September 9, 1922, when the city’s minority quarters burned. The Asia Minor Disaster, as the events of 1922 came to be called, spelled the end of Greek presence in Izmir.

Along the waterfront, Izmir is a cosmopolitan city with wide boulevards, plazas, and plenty of greenery. Fast cars, luxury hotels, and other signs of conspicuous wealth distinguish the coast. Away from the water, however, much of Izmir is a bleak, factory-laden wasteland; on the outskirts, poverty and uncontrolled industrial expansion combine to produce heartbreaking urban squalor. Still, the city is worth visiting for a few days, especially in June, July, and August, when it hosts the International Izmir Festival, attracting world-renowned musical, dance, and theater performers. Unlike most Aegean towns, summer in Izmir is low season, as many of the city’s well-to-do leave town for beach resorts like Foca and Dikili.