The largest city in southeast Turkey has a rich heritage dating back to the Stone Age. Yet apart from its fortress, floodlit at night upon a man-made hill, this heritage is giving way to a veneer of modernity. Today, Gaziantep competes with its neighbors for pre-eminence in trade and industry. At night, locals flock to Centenary Park, complete with water gardens, bike tracks, shopping, and a cinema. Beyond the city, a fertile plain of pistachios, olive trees, and vineyards extends in all directions. Gaziantep is a crossroads town for travelers heading west to the Mediterranean coast, south to Antakya and Syria, or east to Van. The Turkish Grand National Assembly granted the town its epithet Gazi (war hero/veteran) in 1921 for its resistance to foreign occupation during the War of Independence.

The waters of Lake Van are a magical reflecting pool, turquoise by day, red at sunset, and quicksilver after dusk. The silken iridescence of this inland sea comes from its alkaline soda waters, but the mountains and castles along its shores reflect the millennia of volcanic and human activity” that have shaped the region. For 3000 years, the area around Lake Van has been Eastern Turkey’s most vibrant and fascinating cultural center. In approximately 800 BC, the Urartian Kings established their capital here, building impressive citadels and canals throughout the region. Van’s strategic location on the Silk Road (İpek Yol) ensured prosperity and power for its rulers. After the Urartians came the Assyrians, Persians, and Armenians, before the Selçuk and then the Ottoman Turks. In the 20th century, Van witnessed the most tragic chapter in the Turkish Armenian conflict.

An uninspiring town in a stunning location, Tatvan hugs the eastern end of Lake Van and offers a launch point for a trip to Turkey’s second, secretive Nemrut Dağ. No, not the place with the big stone heads: this Nemrut is an inactive volcano that holds a breathtaking series of lakes (Nemrut Gölü), and hot springs in a volcanic crater. A dusty, one-horse town, Tatvan is nonetheless a convenient base for exploring the Selçuk tombs and Urartrian fortresses of Lake Van’s north coasts.Set back from the water, Tatvan’s services are all along Cumhuriyet Cad., its main thoroughfare, centered around Tatvan Park and the main dolmuş lot opposite. The new otogar is on the highway 1km north of town, but most buses will chop you at the town center. The tourist office is just above the dolmuş/taxi lot. Mehmet Salici (832 42 28) runs tours of the lake area out of the office. Pharmacies and ATMs can be found near the park, and the PIT (open 7am-11pm) is directly across the street.Apart from the flagship hotel Kardelen O, across from the PTT, most are bare- bones budget joints. The Kardelen has large, bright, freshly-painted rooms, TVs, minibars, a pleasant terrace restaurant, along with a pool hall. Mehmet, the concierge, speaks English and organizes tours. (827 95 00. Rooms $15 per person.) The best option among the midrange accommodations is Hotel Altilar , Cumhuriyet Cad. No. 164, which offers clean rooms with baths and TV’s. (827 40 96. Singles $8, doubles $13.) You would be wise to inspect the kitchens of Tatvan’s lokantas before you eat. Berivan Restaurant , Cumhuriyet Cad. No. 12, (827 10 51), serves meals from $1-2. Some of the best dining is actually ‘¿Vikm. out of town, along the north shore of the lake. Supan Adabag Restaurant has fresh, tasty kebaps ($3) and a breezy view- of the lake denied to downtown Tatvan diners.

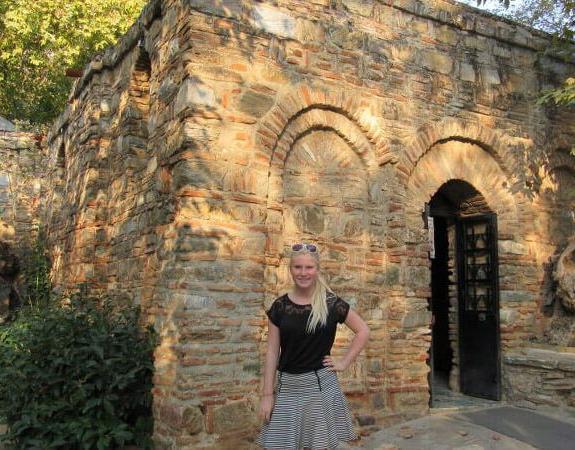

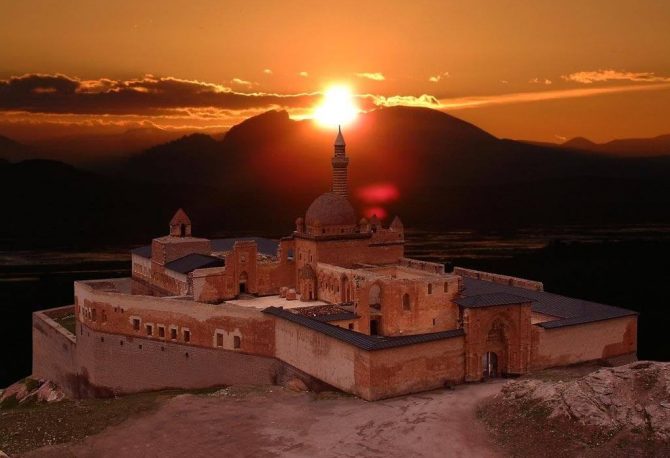

Turkey’s portion of the Silk Road ends at Doğubeyazıt, a frontier town that has lured increasing numbers of independent travelers to its ruins and rugged terrain. Flanked to the north by the majestic double peaks of Ağri Dağ (Mt. Ararat) and to the south by the hilltop İşak Paşa Palace, the valley between teems with traffic from Turkey to Iran. High and dry, with a frontier feel and a dusty, windblown main street, Doğubeyazıt also represents the northeastern border of Turkey’s Kurdistan the “nation” of ethnic Kurds that stretches into Iraq. Visitors in late April may get a chance to take part in the annual Kurdish nevros festival, but visitors can enjoy warm Kurdish hospitality and traditional cuisine year-round.

Erzincan lies in the fertile Euphrates River valley, surrounded by wildflowers and poplar groves and bordered by the Munzur range to the south and the Western extensions of the Kaçkars to the north. An ancient city robbed of its quaintness by a series of natural disasters, Erzincan has quickly rebuilt itself: in 1939, it suffered one of the most devastating earthquakes in Turkish history, which killed more than 30,000 people. A later quake in 1993 (plus a few in between) destroyed most of the buildings of historical interest. The town, however, has recovered rapidly, and commercial and civil industry are booming throughout the downtown area. Students from all over Turkey attend Erzincan’s Atatürk University, lending the town a vibrant and somewhat cosmopolitan air. A clean and energetic town, Erzincan is an ideal base for exploring the natural beauty of the upper Euphrates valley.

Turkey’s highest city, Erzurum sits on an elevated plateau bounded by three mountain ranges. The mountains form the three river valleys that have ensured Erzurum’s strategic importance for millennia, with the Aras winding east from the Palandöken mountains to the Caspian Sea, the Tortum Çay coursing north from the through the Çoruh Valley to the Black Sea, and the Euphrates carving west from the Dumlu Mountains through Central Anatolia. At 1950m elevation, the climate tends toward extremes: winter snowfall is heavy and deep, and summers can be sweltering. Even in the temperate spring and fall, travelers should be prepared for flash hailstorms. When not hailing, however, the sky is clear and bright and the countryside pleasant, making Erzurum an excellent base for daytrips to the southern Georgian churches and the hot springs of Pasinler.

Just 9km off the main Artvin-Erzurum road, Yusufeli offers sweet solace from the urbanization and illicit commerce of its larger neighbors. The town straddles the Barhal River just before its intersection with the Çoruh, leaving hanging pedestrian bridges and terrace cafes jutting out over the rushing rapids. On the drive inland from Artvin, the Çoruh River narrows and the valley walls steepen into dry, crumbling spires and cliffs as the water gets rougher. Yusufeli hosted the world whitewater rafting championships in 1993, and the nearby river includes Grade V and VI rapids. Nearby Georgian churches and close proximity to Tekkale and Barhal make Yusufeli the perfect base from which to explore the Kaçkar region.

Ankara’s history and character sometimes lead would-be visitors to dismiss the city as afunctional, soulless capital city. Such an attitude ignores 3200 years of history and Ankara’s place as Turkey’s premier college town. Its old houses and twisting streets lie in a confusing tangle beneath imposing Byzantine walls, concealing dozens of cafes with breathtaking views, while nearby Kızılay, the main student area, has bars and an active nightlife to suit all tastes.

Though officially known as Şanlıurfa (Glorious Urfa), for its contribution to the struggle for Turkey’s independence, this city is known as Peygamberler Şehri to Muslims: City of Prophets. Urfa is a place of pilgrimage, being the putative birthplace of Abraham and the home of the prophet Job, as well as ten other Biblical figures including as Jethro, Joseph, and Moses. Şanlıurfa is old, mind-bogglingly old, with newly-excavated temples at Göbeklitepe dating back to 9000 B.C. Urfa has changed hands many times along the millennia: from Hitit to Assyrian to Alexandrine to Commagene, Aramacn, Roman, Persian, Byzantine, Arab, Latin, Selçuk, before finally joining the Ottoman Empire in 1637. These diverse influences have simmered gently in the city to form a distinctive style of architecture, still visible today. Meandering through old narrow streets, you can still catch glimpses of the old stone carvings. Urfa’s mansions have open courtyards and cool shaded summer terraces, elegantly carved with crescent moons and vine leaves. Recently, many old mansions have been restored as guest houses and restaurants, and a series of green parks and çay gardens have sprung up.

Malatya (pop. 800,000) is Turkey’s apricot capital and birthplace of Turkey’s second president. The city lies in a fertile basin, shadowed by a barren range that points the way to the magnificent Nemrut Dagi ruins. While most approaches are unremarkable, the journey from the south (Adana or Maras) is characterized by cascade carved gorges. Malatya’s football team, which has only recently joined Turkey’s top tier, is the latest jewel in the crown of this glittering modern city. Malatya’s open parks and wide, tree-lined boulevards are as pleasant to stroll through as the narrow corridors of its famous apricot bazaar.

Most travelers arrive in Malatya’s palatial otogar, 3km west of town. Dolmuş connect this station with downtown, passing the train station on the way.