PEOPLE DEMOGRAPHICS

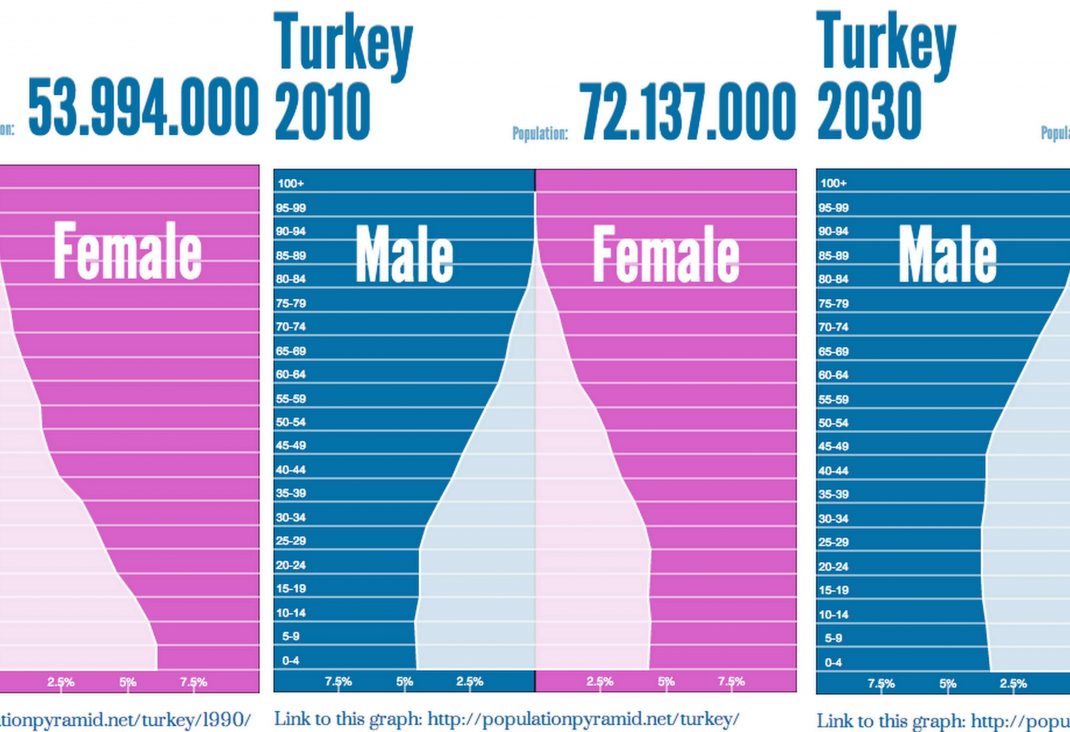

Turkey’s population numbers approximately 67 million. Around 75 percent of the population lives in urban areas. The large majority of Turkey’s people are Sunni Muslim Turks. Muslim Kurds comprise a substantial minority. Other minorities include Armenians, Jews, the Alevi, the Laz, the Hemsin, and the Circassians.

TURKS

The nomadic ancestors of the modem Turks came from Central Asia in the 11th century AD and conquered Arab and Byzantine empires. At first shamanism, the early Turks dabbled in all of the great religions of the region, including Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity, before settling on Islam. Turks have a proud military tradition that remains important today.

KURDS

The 1999 capture and conviction of Kurdish guerilla leader Abdüllah Öcalan brought increasing international attention to the Kurds, the largest ethnic group in the world without its own nation. An estimated 20 million Kurds live in the regions of eastern Turkey, northern Syria, Iraq, and northern Iran. Between twelve and fifteen million live in Turkey alone, comprising nearly 25% of the population. Divided by international borders and along religious, linguistic, and political lines, the Kurds arc far from homogenous. The Kurdish language has its roots in northwestern Iran. Of the three distinct dialects spoken by Kurds today, Kurmanji is the most widely spoken in Turkey. Traditionally, the Kurds pursued a nomadic lifestyle of pastoralism, herding sheep and goats and raising horses. After World War I, urbanization and the division of Kurdish lands into disparate nations prevented customary migrations and forced many to settle in towns; however, nomadic lifestyles persist within the more remote regions of Eastern Turkey.

Although they fought alongside Atatürk’s forces to establish a Turkish state, the Kurds were repaid not with the foundation of an independent Kurdistan, but with the new’ Turkish government’s policy of enforced assimilation an attempt to create a unified Turkish nation. Kurdish revolts in the 20s and 30s were met with the executions, deportations, and razing of villages that began armed control of Eastern Turkey. By 1925 the government had outlawed the Kurdish language, forbidden traditional dress in cities, and encouraged Kurdish migration to the country’s urbanized western regions. Kurdish newspapers, television, and radio were also prohibited. Refusing to recognize the Kurds’ distinct ethnicity, the Turkish government referred to Kurds as “mountain Turks” until the 1991 Gulf War.

Disaffected by their plight, many Kurds sought to voice their objections and demands through political means. The most famous and extremist Kurdish political group is the PKK or Worker’s Party of Kurdistan. Founded by political science student Abdullah Öcalan in 1978, the PKK pledged itself to armed struggle in hopes of forming an independent and Marxist Kurdish state.

In the middle of 80s, the PKK began to attack Turkish towns in the east and prominent Turkish officials. In response, the government, declared martial law in the affected areas and armed loyal Kurds to create a defensive force known as the village guards. By taking advantage of the lack of Kurdish unity, the government helped to turn Kurds against one another, and the PKK increasingly attacked Kurds who had associated with the Turkish system. In the early 1990s, the PKK undertook a series of bombings in heavily touristed coastal cities. These bombs were meant to bring attention to the Kurdish cause by bruising the country’s high-revenue tourist industry. The government responded harshly with its own bombings, village evacuations, jailings (often in violation of international human rights legislation), and executions (often under mysterious conditions). By 19.99, the continuing conflict had claimed over 30,000 lives.

International perception of the Kurdish issue in recent years has changed from anti-PKK sentiment to criticism of Turkey’s human rights policies. The state is tom between its desire to completely quell Kurdish separatism and its interest in placating the international community and the European Union. There has, for instance, been some progress for the Kurds. Though the Kurdish language is still banned in schools and broadcasts, a 1991 decision now permits its use in unofficial settings. The Turkish army, however, has maintained its tough stance against terrorist activities, launching offensives to eradicate the PKK. As a testament to the army’s success in weakening the PKK, Öcalan was preparing for a compromise before his capture in February 1999. Though Öcalan offered to broker a ceasefire in exchange for his life and Kurdish minority rights, the court sentenced him to death in June 1999. After the verdict, a renewed outbreak of bombings ensued. Since then, the PKK has announced that it would no longer resort to violence.

ARMENIANS

The ruins of Ani (50km east of Kars), a city that rivaled its western brother Constantinople in size, grandeur, and population, still remain to prove the millennial legacy of Armenians in Central Anatolia. Armenians lived under Ottoman rule until the 19th century, when Armenian separatist groups were founded with the hope of establishing an independent Armenian state, often through acts of terrorism.

At the outset of World War I, alliance with the Russians offered hope for Armenian independence, and a few thousand Armenians enlisted in the Russian armed forces. On April 20, 1915, Armenians revolted in Van, seizing the city’s fortress in anticipation of Russian back-up. Fearing the Armenians’ alliance with Russia, the Ottoman government (or the military acting independently) initiated a program of deportation, relocating Armenians to the Syrian desert. Hundreds of thousands were killed outright during the relocation, and much more died on the march.

Today, both sides dispute the facts, causes, and repercussions of this event. Armenian casualties are estimated at about two million, though the Turkish government insists on a much lower figure. The Turkish government denies that the program was officially sanctioned and claims that it was a spontaneous military response to the threat posed by the Armenians’ treasonous alliance with Russia. They assert that, the high death count was largely a result of inter-communal warfare between Armenians and Kurds and that many Turks were killed as well. In any event, the Turkish government claims that all state records of orders and decrees concerning the slaughter, known as “tercih” in Turkish, have been lost or corrupted. Other international sources believe that the incident was the first state- sanctioned genocide of the 20th century.

Armenians and their supporters demand that Turkey officially recognizes the genocide and provide some form of apology or compensation. In the 1980s a group known as the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) murdered over 30 Turkish diplomats to bring attention to these demands. Many Turks today, however, feel that it is unrealistic and impossible for them to assume responsibility for actions of the Ottomans of almost a century ago.

JEWS

Jews represent a population of about 26,000 in Turkey today, concentrated mainly in Istanbul and with large communities in Izmir and Ankara. 96% of Turkish Jews are of Sephardic descent, tracing their lineage back to those who fled Iberia in the

15th century. Some fled the Inquisition, but the majority were expelled after the Christian Reconquista of Spain and Portugal in 1492. (The term “Sephardic” comes from the Hebrew word for “Spain,” though it was originally applied to the area around Sardis to which Jews fled after Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest of Jerusalem.) The older generation of Sephardic Jews still speaks Ladino, a variant of the 15th-century Judeo-Spanish language, while the Ashkenazis speak Yiddish and the Karaites speak Greek. Dating to the early 15th century, the Ahrida Synagogue in the Balat neighborhood is the oldest of Istanbul’s 16 synagogues in use today.

Throughout the Holocaust, Turkey extended open refuge to Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, and notable Jewish intellectuals were invited to find safety behind Turkish borders. Upon the establishment of an Israeli state in 1948, 30,000 Jews emigrated from Turkey, and the population has continued to decline steadily.

ALEVI

The Alevi are Shi’ite Muslims who adhere to simple moral norms rather than the Sharia (Islamic law) and the traditional pillars of Islam. Elements of pre-Islamic Turkish and Persian religions infuse Alevi practice with more mysticism than is present in Sunni Islam. The Alevi believe in direct communion with God without the intermediary of the prayer leader. Thus, the only religious figure is the advice-giving dede (wise man). Much like the dervishes, the Alevi celebrate their religion through music and dance in religious ceremonies known as Cem. That men and women perform these dances together have traditionally been a source of contempt among Sunni Muslims, who emphasize the potential for unholy activities.

The Alevi are estimated to comprise between 15-25% of the population and can be divided into four primary groups based on language: the Azerbaijani Turkish speakers of Eastern Turkey, the Arabic speakers of Southern Turkey, and the more populous Kurdish- and Turkish-speaking groups, concentrated in southeastern and central Anatolia, respectively.

The Alevi have been long-time supporters of the secularization of the state; they embraced Kemalism since it allowed them to fit into mainstream Turkish society, but Sunni-Alevi clashes in the 1970s demonstrated to Turkish officials the difficulty of realizing the unified, homogenous, and secular state that Ataturk had envisioned. Because of their greater visibility in recent years, the Alevi have become increasingly vulnerable to violence from certain conservative groups, inspiring some radicalized Alevis to draw parallels between their own situation and that of the Kurds. Both stand as obstacles to the nationalistic, anti-pluralistic conservative agenda of Turkey’s most extreme factions.

THE LAZ, THE HEMŞİN, AND THE CIRCASSIANS

The Laz, though present throughout Turkey, are concentrated largely in the eastern regions of the Black Sea coast near the border with Georgia. Numbering approximately 250,000, the Laz have a reputation for being successful businesspeople, as they own and operate many of the Black Sea shipping companies. Their relative affluence often makes them the subject of envy and ethnic jokes among young Turks. It seems likely that they migrated from the war-tom region of Abkhazia, the westernmost province of the Republic of Georgia, in the 16th century when they were driven west to Turkey by Arab invaders. Christians until the 16th century, the Laz gradually converted to Islam and became so assimilated that most have completely forgotten their religious heritage. Related to Georgian, the Laz language, Lazuri, was purely a spoken one until the 1960s, when its alphabet was codified as a combination of Georgian and Latin letters.

The Hemşin people, historically concentrated around Ayder in northeastern Anatolia, are Caucasians like the Laz. Traditional Hemşin villages are suffering from the flight of their youth to urban centers there are only about 15,000 Hemşin people left in the Ayder region. There is some speculation that the Hemşin might have originated in the area of modern-day Armenia. Like the Laz, the Hemşin people were originally Christian, and even now, their version of Islam is much more relaxed than that of most of their ethnic Turkish neighbors. The Hemşin are traditionally beekeepers and pastry makers.

The Circassians (Çerkeş in Turkish) originated in the northern Caucasus region. With several hundred thousand members, this is the largest Caucasian minority group in Turkey. Most Circassians today are descendants of refugees who were forced to leave their homelands during the 19th-century Russian occupation. The fall of the Soviet Union seemed at first to be a likely catalyst for Circassian repatriation, but the 1992 war in Abkhazia and the subsequent wars in Chechnya served as major deterrents. During the last decade, the Turkish Circassian communities have become more visible and are experiencing a revitalization.

Leave a Reply